21 Open Innovation

Open innovation is a way of organizing innovation built on the idea that firms should use both internal and external ideas, knowledge, and technologies to improve their innovation activities (Bogers et al., 2019; Chesbrough et al., 2006). The notion of open innovation is built on the assumption that the best ideas for innovation are unlikely to come from a single firm, nor do the most talented people work for only one organization (Chesbrough, 2003). Implicit in open innovation is the idea that no firm can truly innovate in isolation, but rather must engage with a plethora of actors and partners to acquire ideas and resources from the external environment that ultimately help the firm stay ahead of competitors. This seemingly simple yet powerful idea that focuses on harnessing and enhancing the firm’s internal innovation capabilities and exploring new business models has become an imperative for orchestrating innovation in smart tourism firms.

21.1 What Is Open Innovation?

The term open innovation was first enunciated by Professor Chesbrough in 2003, who proposed a paradigm shift in contrast to closed or in-house innovation, which is the one developed internally by the firm’s R&D department. Since then, the concept has continued to evolve and has been redefined by Chesbrough and Bogers as “a distributed innovation process based on purposively managed knowledge flows across organizational boundaries, using pecuniary and non-pecuniary mechanisms in line with the organization’s business model” (Chesbrough & Bogers, 2014).

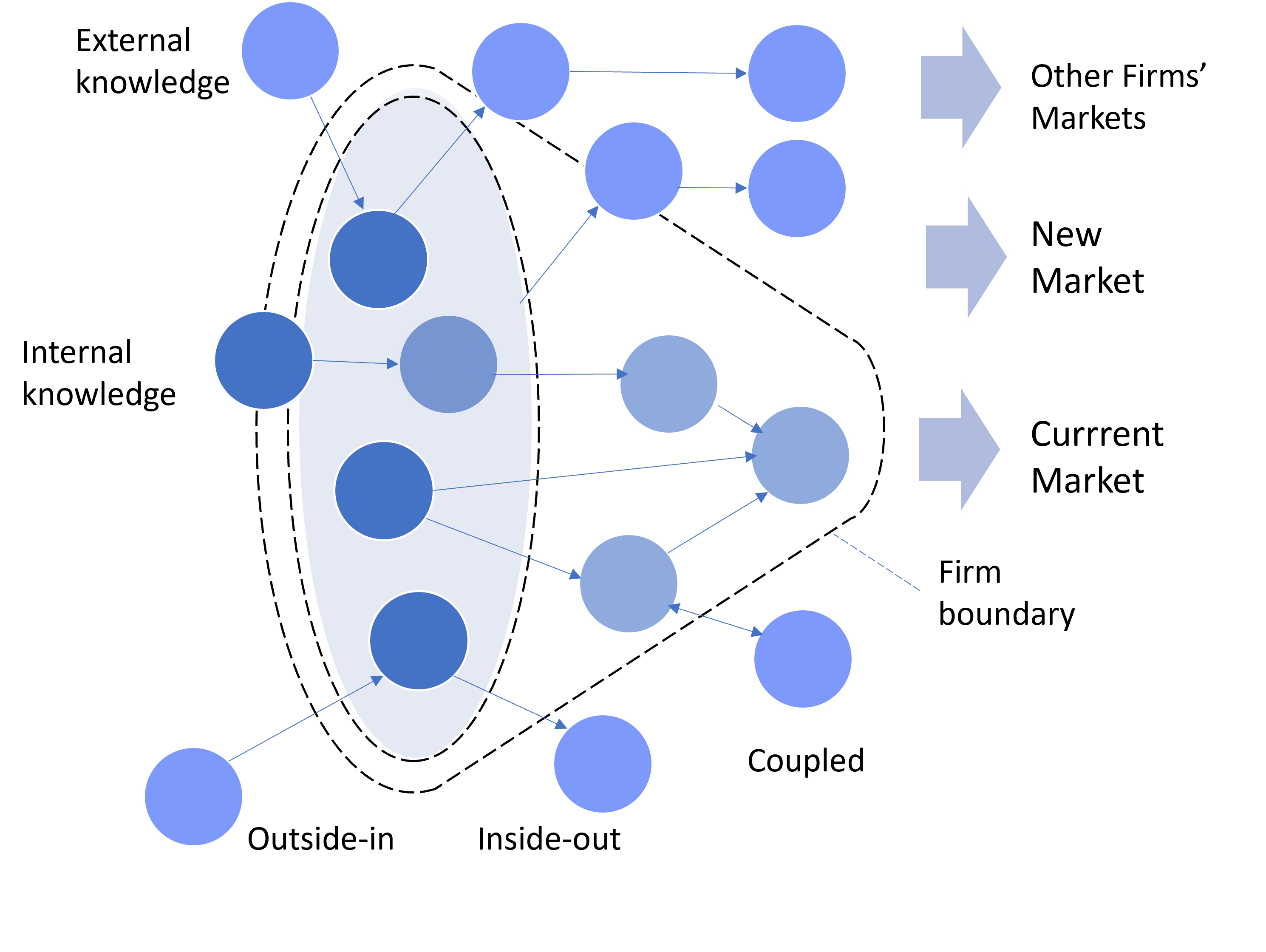

According to the open innovation paradigm, the geographical footprint of innovation has changed dramatically, and the sources of ideas and knowledge have spread throughout the world. Moreover, the boundaries between firms, and between firms and their external environment, have become permeable to the point that firms can create value more effectively by integrating a broad variety of entities into their innovation process, such as suppliers, customers, experts, competitors, universities, consultants, etc. (Chesbrough, 2003). Hence, open innovation enriches the traditional innovation funnel, where the boundaries are typically closed, by bringing the external environment inside the funnel, so that innovations can even be exploited outside the firm (Fig. 21.1) (Pellizzoni et al., 2019). In other words, firms should not rely solely on their own internal research and ideas but also seek outside sources that can boost their innovation. This is known as the outside-in mode of open innovation and to embrace it firms must equip themselves with mechanisms to attract external actors and engage them in tasks that enrich the firm’s value propositions. Many times these mechanisms involve the construction of platforms that connect the actors of innovation and integrate useful technologies to solve real problems. Other times firms rely on intermediate actors who, through their expertise and knowledge of the R&D system, foster connections between entities and help orchestrate the key resources that facilitate open innovation. Ultimately, the outside-in process of open innovation enriches the traditional innovation funnel by transcending organizational boundaries and making it permeable rather than closed. With open innovation, ideas, technologies, and solutions from the external environment can be brought into the funnel and the innovations thus developed can be exploited outside the firm.

While the outside-in (or inbound) direction is perhaps the best known and most developed mode of open innovation, it is not the only one. There is also an inside-out (or outbound) mode and a coupled mode, which involves combined inputs and outputs of knowledge between innovation actors. The inside-out mode considers the firm’s intellectual property (IP) as an enabler to access external ideas and allow others to use the firm’s own ideas. This is possible because there are intellectual property rights (IPR) that grant their owners the right to exploit and share them with third parties under the established terms. Licensing a third party to exploit IPR in exchange for a royalty is a very common practice that encourages others to adopt the firm’s own technology and know-how. This, in turn, can lead the firm to explore new business models that can bring new revenue streams and mitigate some of the risks assumed in technology development processes. Contrary to popular belief, the inside-out approach does not mean that the role of IPR loses its importance or is counterproductive – quite the opposite. It has been shown that collaboration and intellectual property rights are not substitutes but complementary to facilitate an open innovation process, and that firms become more collaborative after receiving a patent than before receiving it (Zobel et al., 2016).

The combination of the outside-in and the inside-out modes leads to the so-called coupled mode of open innovation. This mode requires that both processes occur simultaneously, which usually calls for some type of partnership agreement between firms, such as strategic alliances, joint ventures, or spin-offs, to jointly develop and commercialize innovations. Among the mechanisms used to implement a coupled open innovation process are the creation of communities of practice, the establishment of consortiums, and networks.

Today, open innovation includes a wide variety of different activities, from collaborations between industry and academia, to the development of open source software, crowdsourcing, or the relationships between corporations and start-ups (Bogers et al., 2019). There are firms that are even using open innovation within the more general framework of (corporate) innovation and entrepreneurship activities to drive change in organizational culture, such as when developing new products and services that involve multiple groups of stakeholders (e.g., customers, suppliers, competitors) with a view to increasing the efficiency and effectiveness of new development processes. In addition, firms are applying the exchange of ideas, knowledge, and technologies between various actors in all phases of the innovation process, including R&D, production, design, marketing, and innovation commercialization (Burchardt & Maisch, 2019). This has led to open innovation being considered an essential practice for any firm that relies on the potential of external ideas, knowledge, and technologies to create value. Tourism firms are increasingly motivated to integrate open innovation into their overall business strategy and combine external resources and skills with their internal capabilities, implementing specific processes that enhance learning and collaboration through networks and ecosystems.

21.2 Drivers of Open Innovation

Although open innovation emerges as a groundbreaking paradigm to which smart firms should start giving their full attention, the truth is that organizations have always relied on some form of external knowledge and ideas to innovate. What has changed is that today almost all firms agree that the best ideas and people are elsewhere, which is explained by the globalization of the business ecosystem, advances in education, and accelerated technological progress. Consequently, open innovation today is qualitatively and quantitatively very different from what it was in the pre-internet era. Knowledge and ideas no longer spring from a few leading innovation centers located in rich countries. Firms can now connect with communities large and small where cutting-edge ideas, knowledge, and technologies are being forged and shared, and new patterns of cross-functional collaboration are emerging. The exchange of knowledge and ideas has thus become tremendously efficient and having access to expertise and finding the right solution to a problem is no longer a matter of having substantial resources, but of knowing where to look at the right moment.

So, what are the main drivers that can accelerate the adoption of open innovation?

Since the 1990s, many global firms have significantly reduced their investment in research, leading to a sharp decline in internal R&D spending. An increasing number of corporate investors now take a short-term view of business, and there are plenty of shareholders who pressure top management to continually cut costs. As firm-driven innovation becomes rarer and technology cycles shorten, it becomes faster and more affordable to turn to external sources of R&D, leaving firms no other choice but to drive open innovation through suppliers, partners, consultants, universities, etc. This is an adverse trend that highlights the growing inability of firms to innovate and for which open innovation is only a “stopgap” solution (Bogers et al., 2019).

A second driver of open innovation has to do with digital technologies, which are significantly revamping the way firms organize innovation. Digital technologies are propelling the flow of vast amounts of information from one place to another and fostering open collaboration between firms to innovate. New ecosystems are emerging characterized by a coordinated collaboration where firms organize to improve their products and services and provide valuable solutions to those who need them. Given the growth that these ecosystems are having, everything seems to suggest that their economic and social impact will continue to increase and shape new forms of open collaboration in the near future (Brunswicker et al., 2015).

Open collaboration between firms opens up new opportunities to explore new business models and exploit emerging innovations. Those with the highest potential are related to the analysis, dissemination, and leverage of large amounts of data being generated by consumer behavior in smart ecosystems and platforms. Big Data thus becomes a key driver that, together with the technological infrastructure that sustains it (e.g., the Internet of Things (IoT)), further accentuates the need for participatory approaches among firms and fosters the emergence of open innovation systems (Burchardt & Maisch, 2019). Furthermore, the ubiquity of digital platforms requires the intertwining of multiple technologies whose level of sophistication and technical complexity means that they cannot be provided by a single vendor. Digital convergence thus becomes an essential commitment that every open digital ecosystem must put into practice. Both the IoT and smart destinations are good examples of this, as they require the orchestration of many types of partnerships and collaborations to be able to offer solutions. Through open innovation it is possible to achieve digital convergence more easily.

Closely related to the above is the role that social media are playing as creators of valuable knowledge assets for firms and as enablers of digital platforms for greater tourists engagement (Del Vecchio, Mele, et al., 2018a). Social media have become a source of intelligence for firms and a highly qualified provider of information on consumption patterns and consumer preferences in real time. The vast amount of data that is generated on social media about the experiences, opinions, and reviews of tourists is a rich source for open innovation and decision-making in tourism firms. However, despite the huge potential of social media for open innovation their use remains rare and firms have not yet reaped significant benefits from their use.

The combination of social media and smart technologies is radically changing firms’ innovation strategies by enabling user empowerment and more participatory innovation processes. As more user knowledge and experiences are collected through social media and smart technologies, they become major players in the open innovation game plan (Brunswicker & Vanhaverbeke, 2015). As a result, the interest of firms in co-creating value with their users and customers is growing, as these too are willing to play an active role in the product and service development process. On the other hand, firms have begun to realize the vital role that users can play in the innovation process and have started to reorient their innovation strategies to harness co-creation opportunities (Jung & tom Dieck, 2017). There are good examples that highlight how users participate in the value co-creation process, from the Walt Disney theme park model, where employees and visitors engage in co-creating experiences, to the IKEA model where customers select, pick-up, transport, and even assemble the items they buy.

In the end, the idea of open innovation has become highly relevant to tourism firms, which have long been leaders in the adoption of innovative services (Abbate & Souca, 2013). Many tourism firms are used to creating value offerings with the collaboration of employees, suppliers, partners, and, especially, customers, who often become co-creators of their own tourism experiences and actively stimulate interactions to explore new ideas and solutions. Turning tourists and visitors from passive recipients of experiences into active participants in product and service development and co-creators of value it is expected to become an important source of competitive advantage for tourism firms in the coming years (Payne et al., 2008). The way in which tourists interact with firms to co-create experiences can be very varied. They can offer ideas, share content, and create their own personalized tourism experiences, with roles ranging from mere facilitators on the periphery of the firm’s innovation process, to become involved as partners or having an active role contributing and exchanging knowledge with the firm. Be that as it may, tourism firms must provide users with co-production, participation, and personalization through appropriate mechanisms of joint exchange and interaction. This will pave the way for the tourist to become a key asset in the firm’s innovation process, and a constant source of useful ideas to co-create opportunities in highly competitive markets (Yin et al., 2021).

21.2.1 Big Data and open innovation

Big Data becomes relevant for innovation when firms realize that external knowledge is a key source of the innovation process. Indeed, Big Data represents an emerging opportunity to improve the effectiveness of open innovation as it unfolds new discoveries and opportunities for entrepreneurship.

The open innovation paradigm can be a suitable approach to manage the large amount of data that is generated every day from different sources and in real time (Del Vecchio, Di Minin, et al., 2018). In fact, the relationship between Big Data and open innovation seems quite natural, as both deal with external sources of information and knowledge that can be highly impactful for business innovation (Del Vecchio, Mele, et al., 2018b). More specifically, Social Big Data, understood as the sum of all the data generated and shared through social media, is increasingly used by firms to acquire external knowledge that can be useful to develop new products, services, methods of distribution, etc. In light of its promising potential, new solutions are needed to make the most of available social data and turbocharge the innovation strategies of large and small firms.

From the perspective of open innovation, Social Big Data makes it easier for firms to create value together with customers and stakeholders by acquiring knowledge that can be used in the innovation process. Since Social Big Data is the result of very diverse and varied data that comes from customers and users with different levels of skills, knowledge, and experiences, open innovation can be a suitable approach to bring this knowledge to the different stages of the firm’s innovation flow, including ideation, R&D, and commercialization (Del Vecchio, Di Minin, et al., 2018). In the ideation stage, Social Big Data can be a relevant source of knowledge about new trends, customer preferences, and acceptance of products and services, which if properly addressed by the firm, can help identify new customer needs and trends. Data generated through social media, when exploited using advanced analytical techniques, can be effective in predicting consumer behavior and confirming market trends, which in turn can support internal R&D and innovation processes, the development of new products and services, as well as improve business models and decision-making. No less important is that social media are an extraordinary promotion and marketing channel used by firms as a showcase for the commercialization of their products and services. Data generated from word of mouth and peer recommendations provides relevant insights into brand reach and perception, as well as user preferences, which can be very valuable for the commercialization and marketing strategies of firms.

Although Big Data challenges all industries, it acquires special relevance in knowledge-intensive industries such as tourism, where it can be a powerful tool to foster innovation and competitiveness and the basis for the development of smart firms. For tourism firms to develop open innovation strategies based on Big Data, it is important that they understand in advance how Big Data can be used to create outbound and inbound business opportunities, how Big Data can impact the absorptive capacity of firms, and how it can contribute to their competitive edge. Ultimately, tourism firms must understand all aspects related to creating value from Big Data (Del Vecchio, Di Minin, et al., 2018). There are many and varied ways to implement open innovation strategies using Big Data. Some may consist of customer communities, idea marketplaces, crowdsourcing, etc., which generate Big Data and allow firms to collect ideas and generate insights from groups of users. The use of sensors and devices in IoT ecosystems, in which a large number of potential contributors engage also represents a good opportunity to collect data and turn it into useful knowledge for firms.

21.2.2 Knowledge management

Competitiveness of tourism firms increasingly depends on the development, use, and exchange of knowledge-based assets from inside and outside the boundaries of the organization. Therefore, the development of strong collaboration and knowledge sharing networks and the application of modern knowledge management techniques become strategic resources to access the information that firms need to drive innovation. It is no coincidence that knowledge exchange plays a central role in the open innovation model, according to which firms identify, manage, exchange, and leverage knowledge effectively to improve their productivity and competitiveness (Laxamanan & Rahim, 2020). In short, firms should deliberately manage the inputs and outputs of knowledge to improve innovation processes and build on the results.

Some of the main knowledge management practices that can be put in place to implement the open innovation paradigm are described below.

Knowledge management in inbound open innovation: Inbound open innovation activities involve managing streams of external information that complement, update, and improve the internal knowledge base available to the firm. Different knowledge management practices allow the firm to integrate internal and external knowledge by collecting, coding, storing, and transferring the knowledge acquired. These practices allow the employees and departments of the firm to explore their competitive environment in search of new ideas and knowledge, as well as to identify potential partners with whom to develop business opportunities to take to the market. It is usually a good idea to develop an internal database, more or less centralized, that contains all the information acquired and that can be reviewed by the members of the organization.

Knowledge management in outbound open innovation: Outbound open innovation processes involve the transfer of information from the firm to the external environment. Such an exchange makes sense when the benefits of transferring knowledge outweigh the potential gains of using it internally to develop new products and services. Knowledge management practices allow firms to decide whether to maintain or sell their knowledge, i.e., when a technology does not deliver the expected results and can be transferred to other firms without its competitive advantage being affected. Those firms that decide to transfer knowledge to other firms must identify in advance who their potential customers are and who they should contact internally. There are market knowledge management practices that help the firm to perform these tasks efficiently.

Knowledge management in coupled open innovation: Coupled open innovation processes address the extensive use of knowledge by different firms, including information inflows and outflows. In this case, firms need knowledge management practices that combine both the acquisition and distribution of knowledge between organizations that can be heterogeneous, with different cultures, information systems, and strategies, which proves a rather challenging and complex task. In this context, it is important for the firm to be aware of the environmental conditions that make organizations engage in knowledge exchange practices, as well as the potential benefits they can obtain from outbound and inbound innovation flows. The use of smart technologies can accelerate the joint development of solutions through communication, collaboration, and participation of firms in iterative processes of generation and exchange of knowledge. At a later stage, the development of joint solutions will require the establishment of governance frameworks at the inter-organizational level to generate sustained positive effects on the innovation performance of firms.

21.2.3 The role of stakeholders

The way in which tourism firms carry out innovation is undergoing a major transformation. The involvement of stakeholders (e.g., customers, suppliers, platforms, authorities) has become central to innovation activities as the open innovation paradigm has taken root in tourism firms. These changes are accentuated by the prominent place that social media occupy in people’s lives and in the activity of firms, which are replacing the traditional top-down approach to innovation with an instantaneous and flexible dialogue on equal terms aimed at co-creating value through innovation.

Social media along with smart technologies are radically changing innovation strategies, creating new user empowerment processes. By empowering users, firms recognize that users can make informed decisions when they have the information and tools to do so. Firms can greatly benefit from the knowledge and experiences of a large number of users thanks to digital tools that are ubiquitous and low cost, allowing users to actively participate in the open innovation workflow. Transparency is another key factor in achieving the right level of empowerment, which may lead users to prefer firms that innovate and provide them with the tools and capabilities to engage (Iglesias-Sánchez et al., 2019).

Therefore, for open innovation to work, flexible and two-way communication channels should be established with stakeholders. Social media have exceptional characteristics that encourage interactions between firms and people and are an ideal interface for identifying opportunities and promoting collaboration among stakeholders, which can lead to the development of highly productive products and services. However, despite the great potential to gather intelligence and become an important source of innovation, tourism firms have not yet sufficiently exploited the use of social media from an open innovation perspective. Interestingly, owners and managers seem to be well aware of the capabilities that these platforms can offer and that their products and services could be significantly improved by collaborating in one way or another with the stakeholders (Iglesias-Sánchez et al., 2019).

21.3 Challenges of Open Innovation

So far, we have seen that open innovation offers enormous potential to improve the knowledge capabilities of the tourism; however, it also poses many challenges that the organization cannot solve on its own and requires the collaboration and participation of other actors. Implementing the open innovation paradigm in the tourism firm is never a quick and easy process, not to mention that the first problems arise as soon as owners and managers try to determine what kind of practices constitute open innovation and what should be done first to improve the firm’s innovation capabilities and competitiveness (Abbate & Souca, 2013). This raises difficult but key questions about how, when, and to what extent to open the boundaries of the firm, and how to find the right partners to start collaborating (Pellizzoni et al., 2019).

Open innovation usually implies an organizational cultural shock that, depending on the depth and intensity of the process, can result in a radical cultural change. The reasons are twofold: on the one hand cultural change is required so that the firm can harness all the benefits that open innovation promises; on the other hand, the application of open innovation practices in the firm implies changes that impact the culture of the organization (Burchardt & Maisch, 2019). Moreover, the impact that open innovation can have on the organizational culture depends on the degree of openness that the firm has when implementing the open innovation model, in such a way that the more open, the less impact on the culture. Culture is also affected by the frequency and duration of collaborations, so that when the firm regularly engages with external actors, the changes produced by the implementation of open innovation are smoother, regardless of the industry in which it operates (Bageac et al., 2020).

How organizations approach the process of implementing open innovation is another major challenge for the firm. It is not the same to address open innovation from the top down than from the bottom up. In general, the top-down approach is more desirable than the bottom-up approach, as this reinforces the development of open innovation practices within the organization. In those organizations where the introduction of open innovation paradigm is a novelty or involves time-consuming cultural changes, it is more effective to approach open innovation from the top down. In decentralized organizations, the successful implementation of open innovation will require strong leadership by top management, and a well-established culture based on the principles of autonomy and freedom in decision-making.

Once the firm has started to develop open innovation practices, it faces the need to create specific organizational structures that support the innovation workflow and extend achievements to all levels of the organization. These structures should focus on identifying knowledge opportunities that exist outside the firm and establishing explicit processes to acquire and transfer them within the organization. On other occasions, these structures should aim at creating connections with external agents and establishing collaborations with them that involve inflows and outflows of knowledge. In general, the units dedicated to open innovation in most of the organizations where they exist are small and characterized by their flexibility, responsiveness, and the ability to lead technical projects collaboratively (Bageac et al., 2020).

The possibilities of open innovation have been strongly boosted by digital technologies. New mechanisms for collaboration and interaction between firms are now possible supported by web-based software tools and digital services that foster the culture of openness and make open innovation practicable at all stages of the innovation process. These tools range from real-time conversation (e.g., Skype, Zoom), group writing applications (e.g., Google Drive, Teams), cloud document sharing (e.g., OneDrive, Dropbox), and advanced integrated workspaces (e.g., Slack). Most of the applications are provided as a freemium model.

Smart technologies are making possible the combination of open innovation practices and Big Data in the quest for firms to find new business opportunities and creating competitive advantages. In fact, Big Data and open innovation have their own challenges that become even more considerable and complex when mixed. This powerful combination poses significant challenges to the skills and knowledge of the workforce required to create and capture data that can be used for business innovation. Firms today must be able to collect, store, organize, process, and, above all, analyze, visualize, and interpret data, and they need the right people to accomplish all these complex tasks. The skills challenge is further amplified when data is used to perform open innovation processes that involve multiple actors. This is particularly relevant for SMEs for whom finding qualified personnel is not only difficult but also very expensive, so they will often need to turn to outsourcing practices.

The challenges that arise from the massive use of data for open innovation do not end here. Some of the most important ones have to do with the ability of firms to work with true and reliable data, both internal and external. Data for open innovation comes from multiple and often open sources that can be affected by various biases and inconsistencies. The consequences of unreliable, biased, or false data for the innovation process can be disastrous and lead to erroneous conclusions that can severely affect the performance of the firm in the marketplace. Owners and managers need to be aware of the importance of good data and spend time and resources to prepare their data mix well before bringing it into the innovation process, thus learning when to trust the results and when to criticize them.

Data privacy and security are also key challenges when firms work with Big Data and to which owners and managers must pay special attention if they are to be used in open innovation processes. This is especially relevant since open innovation involves multiple data sources from actors with diverse information and data management systems, some of which may contain weak processes that can limit reliable access to information and knowledge sharing. To overcome these risks that can arise throughout the firm data collection process, the open innovation paradigm encourages systems integration as a solution that can deliver even more competitive edge when it takes the form of ecosystems. However, systems integration is a major challenge that requires extensive cross-firm collaboration given the considerable heterogeneity of tools and management techniques associated with IT, knowledge management, and open innovation.

All the challenges above are further emphasized when it comes to SMEs that have limited resources to manage innovation processes or lack a structured approach to innovation. Often, owners and managers have few skills in or little knowledge about open innovation methods, so implementing an open innovation approach and coordinating collaboration with multiple actors becomes a challenging task for SMEs. In addition, the maturity period required for innovation initiatives performed by SMEs is usually much shorter than that of large firms, so they will tend to focus more on obtaining results that can be exploited in the short term than in sourcing the best possible innovations. Despite these particularities, SMEs generally have more agile and flexible decision-making processes in place and are capable of reacting to changes in their environment with greater determination, which makes them good candidates to adopt open innovation strategies (Torchia & Calabrò, 2019).

The benefits that SMEs can derive from open innovation practices are nonetheless significant. Collaborating with other SMEs or participating in clusters of firms can lead firms to break down traditional barriers and operate in the market as if they had a greater size and capabilities (i.e., better access to technological, financial, and human resources at low cost). Building partnerships of SMEs to work on open innovation also encourages member firms to innovate, allows them to share risks and sunk costs of failed projects and, ultimately, gives them the chance to benefit from the complementary capabilities and resources of others. However, none of this means that the firm’s R&D department should cease to exist when the open innovation paradigm is implemented; quite the opposite, the in-house R&D department should acquire an even more decisive role under the open innovation paradigm. In fact, both open innovation and internal R&D are to be considered complementary. The real challenge is for the firm to develop absorptive capacity to recognize, acquire, and transfer knowledge and technology from external sources on the basis of its own expertise and know-how (Bogers et al., 2019).

Finally, open innovation is not without its drawbacks. Keep in mind that once a firm’s knowledge assets are made available to other organizations to exploit, intellectual property can be difficult to protect and the benefits of innovation hard to capture (Abbate & Souca, 2013). Furthermore, the successful implementation of an open innovation strategy is based on the firm having a business model in place that is capable of retaining the value derived from innovation. Unless the firm has adequately addressed this important circumstance, open innovation can do more harm than good for the firm.

21.4 Agility and Open Innovation

The firms that best capitalize on open innovation are those that have the necessary organizational flexibility to restructure their processes, strategies, and business models in pursuit of the principles of the open innovation paradigm. This means the open innovation paradigm shares many principles and practices with the Agile framework context. Both aim to tear down corporate silos, strengthen open communication and collaboration between teams and people, and respond swiftly to changes in user/customer needs and preferences, and threats from competitors (Liao et al., 2019). User/customer engagement is continuous during the development of open innovation projects and takes place from the very beginning. Digital tools ensure that sharing and collaboration are much easier and that there is an open dialogue between the firm and the key stakeholders along the process.

From the moment the firm gathers complementary knowledge and technologies externally through inbound open innovation processes, it reduces the risks associated with experimentation, thus stimulating innovation, fostering communication with others, and providing greater flexibility in terms of the resources needed to innovate. Firms with greater external knowledge and skills are in a better position to make faster decisions and adapt their operating frameworks to changes in the environment and threats from competitors. In short, inbound open innovation processes positively influence organizational agility, while the latter improves inbound open innovation. The importance of outbound innovation is lower compared to inbound open innovation and the effects of agility on market capitalization are much less pronounced (Liao et al., 2019). Indeed, outbound open innovation is often the result of inbound open innovation. To harness the potential of both inbound open innovation and Agile principles, the firm must develop a culture and organizational set-up that addresses the following critical issues (Burchardt & Maisch, 2019):

Management must buy in: To combine Agile principles and the open innovation paradigm and scale any mixed initiative across the organization, it is critical to gain the commitment and buy-in of the firm’s top management. When top management understands both Agile and open innovation principles and shares the overall goals of the combined initiatives, it is possible to secure the necessary resources to drive open innovation and make critical decisions when needed.

Legal problems must be solved: A common concern of top management when dealing with the open innovation paradigm is the protection of the resources at stake, especially those related to the protection of intellectual property. Questions about how to protect certain data or information, how to establish collaboration agreements with other firms, and how to manage patents and other rights and obligations must be resolved beforehand.

Operational issues must be handled: To act openly, with agility, and more focused on the needs of users/customers, it is vital to align the firm’s operational processes in a different way. The firm will need continuous and deeper access to its customers and users to gain insight about their needs and preferences, it will have to collaborate with other actors with different goals and business models, and incentivize its workforce to share and collaborate, among other things.

Proactive change management to involve all stakeholders: When the firm decides that it is going to implement the open innovation paradigm with Agile principles, all stakeholders must get involved. However, not everyone is ready to work in this way initially. Some won’t know how to do it, others won’t be able to, and there will surely be those who just don’t want to do it. This is why the firm must perform proactive change management in order for all stakeholders to adapt to the new structure of values of the organization.

Decide when to be open and agile: It is not always in the firm’s interest to adopt an Agile and open innovation approach. Many times it can happen that a closed and traditional (waterfall) approach is more appropriate for what the firm needs. Sometimes making the transition to a new culture, new processes, or changing people’s beliefs, habits and customs is simply an exaggerated effort that the firm cannot afford or does not want to make. Firms must be very aware of the pros and cons of implementing open innovation and Agile practices, and decide when is the best time to move forward.

A common way to address the issues above is to embed Agile principles into the hierarchical structures of the organization and progressively move step by step to achieve the desired goals. Owners and managers aiming to support smart organizational transformation will need to play a leadership role that understands, reflects, and promotes learning and creativity and promotes the development of key skills for everyone in the organization with the aim of creating competitive advantages for the firm. The drawbacks and limitations that the combination of open innovation and organizational agility entails for the tourism firm remains to be seen, as more research is needed on this particular topic.

21.5 Tips for Implementing Open Innovation

Although there are many tourism firms fully aware of the usefulness of the open innovation paradigm to drive the transition towards the smart organization, the problem is that firms usually do not have the capacity to put it into practice. Implementing an open innovation strategy in firms little or not used to opening their boundaries to the world, and given the number of factors affected, implies a high complexity. This situation becomes even harder when owners and manager must align the open innovation strategy with the firm’s general business and systems strategy. Despite the obvious difficulties, owners and managers would better be convinced that the development of open innovation is essential to guarantee the continuity of tourism firms (Iglesias-Sánchez et al., 2019).

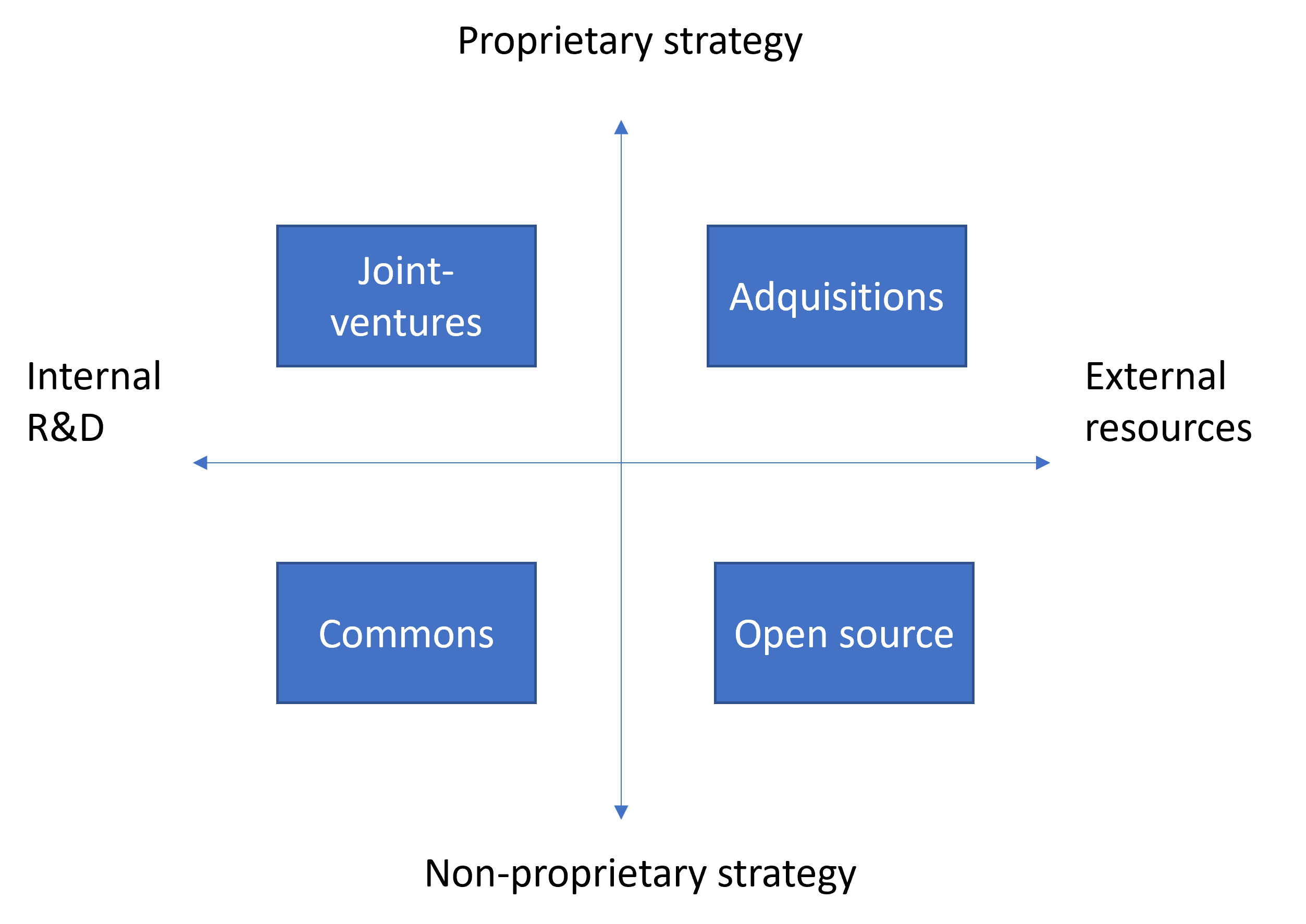

As owners and managers strive to implement open innovation practices, it is very important that they do so thinking about how they will create value (i.e., sourcing knowledge and technologies, establishing partnerships with other firms), and how they are going to capture that value, or put in another way, how they are going to integrate and transfer the new knowledge acquired and how they are going to convert it into new products and services that can be marketed. Unfortunately, there is no single formula that shows firms how to capture value, as every project and context is different (West & Bogers, 2013). However, it is paramount that firms choose an appropriate business model and the right smart technologies to support it. They must determine what knowledge they need to acquire to complement their internal capabilities and with what degree of openness they wish to operate. In the case of underutilized knowledge or technologies, the firm must also decide how much of that knowledge can be made available to other firms and thus generate additional revenue for the business. Ultimately, the firm must find a balance between open and closed innovation and work out how to develop both modes of innovation. Figure 21.2 shows some alternative forms of open innovation that are available to the tourism firm.

For tourism firms to be successful using external knowledge, they will need to realign the organization’s processes and resources to accommodate that new knowledge. This will require developing different organizational practices, such as extensive delegation of responsibilities to people, lateral and vertical communication, and incentives to share knowledge (Bogers et al., 2019). Sometimes it will even be necessary to reshape the organizational culture itself to make it more participatory and collaborative. At times, firms may face the challenge of not finding enough good partners to develop their open innovation initiatives, or perhaps the coordination work required is enormous given the interdependencies that exist between the actors involved. In these cases, it may be better to go it alone. Furthermore, owners and managers should not forget that open innovation has its limits. In situations when the available knowledge is out of date or there are no partners willing to risk a certain project, there is no way that open innovation can help. After all, for open innovation to be successful there must be a rich technology base that can be shared and complemented by the stakeholders.

21.5.1 Organizing for open innovation

There are multiple pathways to implement inbound (outside-in) open innovation that generally depend on the organizational agility of the firm. Very often firms choose between a team-centered model and an individual-centered model (Pellizzoni et al., 2019), although these are not the only viable approaches. The team-centered model is characterized by the presence of a strong managerial role with broad powers, and a clear and well-defined distribution of roles and responsibilities within the organization. Most surely top management commitment is guaranteed, and decisions are made top down, thus allowing open innovation to scale up quickly simply by adding more resources where needed.

The individual-centered model is a completely different approach. People work with a high degree of autonomy and are empowered to make their own decisions, which is reminiscent of Agile management principles and entrepreneurship dynamics. These principles are applied to managing the open innovation initiative and making it evolve through different iterative phases of development where open innovation is progressively learned and understood and gradually refined. The key to an effective implementation of the individual-centered model lies in granting each employee the appropriate level of autonomy to work, organize resources, and make decisions. Unlike the top-down approach, the individual model is bottom up, as employees draw on their formal and informal networks of relationships to accomplish innovation projects. While the individual approach is more affordable than the team-centric approach for the firm (i.e., there is no need to invest in dedicated roles, teams, and resources), it is however more difficult to control and to scale up as the commitment of top management is usually weaker and it is harder to secure the resources needed by open innovation. Nor is it easy to find the right people who can lead the launch of the initiative and develop a culture that permeates the rest of the organization.

There may be times when firms prefer to work with a mixed team and individual approach. In these cases, the firm’s top management commits and participates actively during the first phases of open innovation and creates an ad-hoc structure in charge of managing the open innovation initiative. For their part, managers can decide what projects can be managed in a less structured way, engaging individuals with the ability to lead the tasks. In this way, it is possible to harness the benefits of both models without incurring large costs or causing, at least initially, large impacts on the organization (Pellizzoni et al., 2019).

21.6 Discussion Questions

What impact does “openness” have on tourism firms? What factors influence the decision to adopt one level or another?

How do tourism firms source smart technologies? What factors influence tourism firms’ sourcing methods?

How can tourism firms be classified according to their approach to open innovation?

What kind of complementary external assets do tourism firms usually need to generate greater competitive advantages?

What kind of culture is necessary to unfold open innovation in the tourism firm? What characteristics distinguish that culture?

How and to what extent do tourism firms use social media to develop open innovation?

Are tourism firms concerned about protecting their knowledge assets and making them available to other firms? What are the differences between large tourism firms and SMEs in this regard?